Aanvullingen

Vul deze informatie aan of geef een reactie

‘Sits’ (ook wel: chintz, gerelateerd aan een woord uit het Sanskriet dat gekleurd of gestippeld betekent) werd oorspronkelijk gebruikt voor Indiase kleurechte, lichte, katoenen stoffen. De meestal gebloemde patronen van het vroege sits werden met de hand getekend met een ‘pen’ van bamboe (kalam) met verschillende beitsen en in opeenvolgende verfbaden gekleurd en gefixeerd.[1] De komst van Europeanen in India en de productie van sits voor de Europese markt hadden echter grote invloed op het textiel.

English text below

In een eeuwenlange culturele uitwisseling tussen Europa, India en China werd de definitie van sits opgerekt. De introductie van sits op de Europese markt zorgde voor een versmelting van Europese smaak en Indiase productiemethoden. Deze wisselwerking was constant in beweging, waardoor de oorspronkelijke betekenis van sits als een zorgvuldig, met de hand beschilderd, Indiaas textiel met een glanzende finish, enigszins in de vergetelheid raakte. Tegenwoordig kan elke katoenen of linnen stof sits heten, mits met een gebloemd patroon, gekleurd met kleurechte verfstoffen, gemaakt in of buiten India.

De nieuwe betekenis die sits over de jaren heen heeft verkregen, staat symbool voor een lange dialoog en een interessante vermenging van culturen.

In eerste instantie had de Europese interesse in sits vooral te maken met de waarde van het materiaal als ruilmiddel voor specerijen in Zuidoost-Azië of als halffabricaat dat na verdere bewerking in Europa geëxporteerd kon worden (bijvoorbeeld voor gestikte dekens). Toen handelaren echter de potentie van sits voor gebruik in eigen land zagen, verscheen de stof tegen de 17de-eeuw op de Europese markt.

Sits was in die tijd erg goed te onderscheiden van Europees textiel. Vóór de komst van sits werd in Europa voornamelijk linnen of wol gebruikt voor de bekleding van meubels of het maken van kleding. In vergelijking met de kleurrijke sitsen staken de Europese stoffen echter simpel en gewoontjes af. De Europese patronen werden met blokdruk of borduurwerk gemaakt, wat betekende dat de kleuren verzadigd waren en weinig kleurecht. Sits was echter extreem kleurecht – velen beweerden zelfs dat de kleuren zelfs mooier werden na het wassen.

Zijde, een andere populaire textielsoort in de 17de-eeuw, was alleen verkrijgbaar voor de allerrijksten, terwijl sits een betaalbare status kreeg. Het Indiase textiel maakte het ook voor de minder welgestelden mogelijk om levendige, prachtig gebloemde kleren of bekleding voor het interieur te hebben. Deze onderscheidende eigenschappen van sits verzekerden de populariteit van sits in Europa.

Tegen 1613 was een groeiend aantal Indiase stoffen, waaronder sits, verkrijgbaar in Londen.[2] In 1664 maakte textiel bijna 75% uit van de gehele exporthandel in India en vanaf 1670 werd sits in Europa steeds belangrijker als materiaal voor kleding en interieur.[3] Binnen zestig jaar vanaf het Europese debuut van sits was de geïmporteerde stof zo populair dat het de Franse en Engelse textielindustrieën bedreigde. Door protesten van de industrie legden de Franse en Britse overheden in 1704 een verbod op de import van sits.[4]

De meeste overgebleven sits, die we terugvinden in museumcollecties is het resultaat van een eeuwenlange uitwisseling en intensieve handel. Ondanks de onderscheidende kwaliteiten van sits richtten de handelaren zich hoofdzakelijk op de Europese smaak. De eerste geïmporteerde sitsen, opvallend in hun helderheid en kleurechtheid, waren bedrukt naar Indiase smaak met donkere achtergronden en lichtgekleurde patronen.

Bestellingen die aansloten op regionale smaken waren essentieel voor handelssucces, terwijl de patronen en motieven een “oriëntaal, exotisch aura” behielden.[5] Zo gaven de Hollandse consumenten de voorkeur aan donkerrode kleuren, terwijl crèmekleurige achtergronden erg populair waren in Engeland.

In een complex en doorlopend proces werden Europese stijlkenmerken geïntroduceerd in de ontwerpen van Indiase sits. De vroegste sitsontwerpen bedoeld voor Europese consumptie waren sterk geïnspireerd op gebrocheerde stoffen gebaseerd op bloemmotieven van westerse schilderijen en prenten.[6] Zo stuurde de Britse Oost-Indische Compagnie vanaf 1662 voorbeelden die door de Indiase producenten gekopieerd werden. Deze wederkerige uitwisseling tijdens eeuwen van handel en koloniën creëerde uiteindelijk een cumulatieve stijl die zowel een Europees als Indiaas product was.

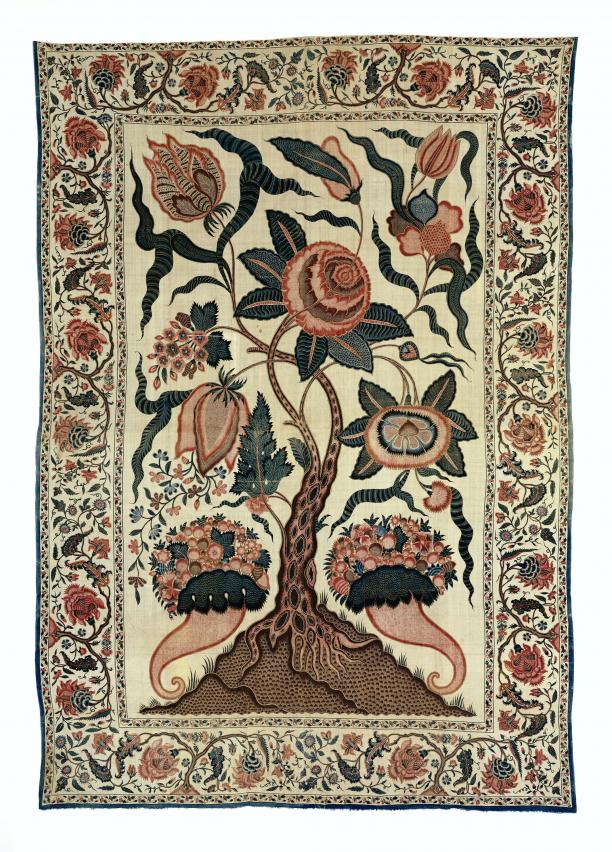

Aan het motief van de levensboom die op de Indiase sits voorkomt zien we de invloeden van deze culturele overdracht goed terug. Het populaire motief laat een kronkelende bloeiende boom zien en vaak een grote variatie aan bloemen en fruit, groeiend op een heuveltje of in een mand. De motieven evolueerden in samenspraak met de ontwikkelende modes in Europa. Toen Chinees behang in de mode kwam, vervingen specifiek Chinese motieven als bamboe, pioenrozen, exotische kwartels en fazanten de normale, fantasierijke planten en vogels.[7]

Europese handelaren moedigden de Indiase textielfabrikanten aan de levensboom anders te plaatsen, zodat het meer overeenkwam met de Europese voorkeur voor symmetrische ontwerpen. Gecombineerd met een witte achtergrond brachten de gekronkelde takken met bloeiende pioenrozen en exotische vogels het oriëntaalse exotisme samen met de Engelse landschapstuinen: ideale afbeeldingen voor wandkleden.

Het meeste textiel dat geëxporteerd werd uit India door de Oost-Indische Compagnieën (EIC (Groot-Brittannië) en VOC) was geen sits, maar eenvoudig, dagelijks textiel bedoeld voor hemden, lakens en andere toepassingen. Sits plaveide ook de weg voor de gewone katoen die we vandaag de dag zo goed kennen. Het uitbundige textiel faciliteerde namelijk het gebruik van katoen voor andere doeleinden, dat een grote impact had op het leven van mensen in het 17de-eeuwse Europa. Geen slechte nalatenschap voor een textielsoort die op een gegeven moment de Europese textielindustrie bedreigde.

Met de uitvinding van spinmachines in de jaren 1760 en '70 kon katoen uit India worden geweven in Groot Brittannië en Europa en verdween de noodzaak van Indiase textielimport. Daarnaast maakte het drukken met koperplaten het mogelijk fijnere patronen en grotere rapporten (herhalingen) te maken. Dit resulteerde in het verval van de Indiase sitsexport. Tegen het einde van de 18e-eeuw was sits grotendeels uit de mode.[8]

English

‘Chintz’, related to a Sanskrit word meaning coloured or spotted, originally referred to the Indian colour fast, light, cotton fabrics. The mostly floral patterns of early chintz were produced by hand drawing with a bamboo ‘pen’ (kalam) and dyed with mordants and resists.[9] But the arrival of Europeans to India would have a profound effect upon the textile as it entered the markets of Europe.

After centuries of exchange and response between European, Indian and Chinese cultures, the definition of chintz expanded. The introduction of chintz into European markets resulted in the fusion of European taste and Indian manufacturing. This synthesis continuously evolved and the original understanding of chintz, as carefully hand painted fabric from India, has been somewhat forgotten. Today, any cotton or linen furnishing fabric depicting a floral pattern, stained with fast colours, made anywhere can be described as chintz.

Through this process, the new meaning of chintz can be interpreted as a symbol of a long conversation and an amalgamation of cultures.

The initial European interest in chintz was concerned with its value as an item for re-export after undergoing further processing or manufacturing in Europe or for use as barter for spices in South East Asia. However, by the seventeenth century, chintz appeared on European markets as traders began to realise the textile’s alternative potential at home.

Chintz was highly distinguishable from the European textiles available at the time. Prior to chintz, linen or wool had been used for the majority of furnishing and clothing in Europe. However, in comparison to chintz, these European textiles appeared flat, drab and plain. The patterns were achieved through block printing or embroidery, which meant the colours were bright as the dyes used were rarely fast. Chintz, on the other hand, was comparatively extremely colour fast, with many claiming the colour was actually enhanced after washing. Silk, another popular textile of the seventeenth century was preserved for those of wealth and privilege, whilst chintz obtained an affordable status. The Indian textile made it possible for the less affluent to own vivid, beautiful floral patterned clothing or soft furnishings.

These distinctions secured the popularity of chintz throughout Europe. By 1613 a small number of Indian textiles, including chintz, were on sale in London with its popularity growing steadily.[10] By 1664, textiles accounted for nearly 75% of the whole export trade from India and from 1670 onwards, chintz started to dominate dress and furnishing fashions into the eighteenth century.[11] Within just sixty years of its European debut, imported chintz was so popular that the huge demand for the material threatened the French and British textile industries. Industry protests led the French and British governments to impose a ban on all imported chintz by 1701.[12]

Most of the surviving chintz we see in museum collections today have developed from centuries of conversation, predominantly resulting from European monologues. Despite the distinctive qualities of chintz, traders in the textile were highly attuned to the fashion tastes of Europe. The first imported chintz, remarkable in their colour brightness and fastness, were, however, printed to Indian taste with dark coloured backgrounds and light coloured patterns. Thus, specific orders catering to regional tastes were essential for successful trade whilst the patterns and motifs retained an “aura of oriental exoticism”.[13] For instance Dutch consumers preferred darker reds, whilst cream backgrounds were popular in Britain.

After a complex and continual process, European stylistic elements were absorbed into Indian chintz design. The earliest chintz designs intended for European consumption were closely based on crewelwork embroideries featuring floral motifs taken from western paintings and prints.[14]

By 1662 the East India Company began sending out designs, or ‘musters’ to be copied by Indian manufacturers. This continuous exchange and response produced a synthetic style that was both the product of Europe and India after centuries of trade and empire.

We can see the transmission of design in the tree of life motif that appears on Indian chintz. The popular motif features a serpentine, blooming tree, usually bearing a wide variety of flowers and fruits, growing from either a hillock, small mound or out of a basket. Coinciding with the fashion tastes of Europe, the motif began to respond and evolve. As Chinese wallpapers became vogue in Europe, distinct Chinese motifs such as bamboos, peonies, exotic quails and pheasants started to replace generic, imaginary plants and birds.[15]

European traders encouraged the Indian textile manufacturers to adjust the positioning of the flowering tree in order to reflect the symmetrical design preferences of Europe. Combined with a white background, the gnarled branches laden with full-blown peonies and exotic birds combined oriental exoticism and English country gardens; perfect design for bedcovers and palampores.

Chintz paved the way for the cotton textile we know and love today. The elaborate textile facilitated the use of cotton for other purposes, which had a profound and positive effect on people’s lives in seventeenth century Europe. Most cloth exported from India by the East India companies were not chintz, but plain, everyday yardage, intended for undershirts, bed-sheets and other utilitarian purposes.

Not a bad legacy for a textile that at one point threatened the European textile industry.

With the invention of spinning machines in the 1760s and 70s, cotton yarn from India could be woven in Britain and Europe. There was no longer a need for import. Additionally, copperplate printing techniques applied to cotton cloth produced finer designs and larger repeats. Combined, the factors resulted in the decline of the Indian chintz trade to Europe. By the end of the eighteenth century, chintz had largely fallen out of fashion.[16]

[1] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 4.

[2] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 14.

[3] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 15.

[4] Peck, Amelia, Bogansky, Amy Elizabeth, Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013, p. 105.

[5] Parasannan, Parthasarathi, Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600-1850, Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 31.

[6] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 21.

[7] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 21.

[8] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 26.

[9] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 4.

[10] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 14.

[11] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 15.

[12] Peck, Amelia, Bogansky, Amy Elizabeth, Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013, p. 105.

[13] Parasannan, Parthasarathi, Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600-1850, Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 31.

[14] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 21.

[15] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 21.

[16] Crill, Rosemary, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, V&A Publishing, London, 2008, p. 26.

Vul deze informatie aan of geef een reactie

Terwijl sits aan het einde van de 18de eeuw verdween uit de algemene mode, werd het een kenmerkende stof voor bepaalde kledingstukken in streekgebonden drachten. Daarvan zijn talloze voorbeelden te zien in de musea met een streekdrachtencollectie, zoals het Nederlands Openluchtmuseum. Maar ook in bijvoorbeeld Spakenburg worden bij speciale gelegenheden de mooiste kraplappen gedragen. En die zijn van 18de handgeschilderde sits uit India. Deze stoffen worden tussen alle latere navolgingen nog feilloos herkend door de draagsters van streekdracht.

Nu lijkt het wel vaak of de meeste sitsen in tinten rood en blauw zijn gemaakt. Niet alle kleuren op de Indiase sitsen waren even kleurecht. Bij stoffen waar geel in zat verdween dit vaak bij het wassen. Daardoor verdwenen ook de groene (geel over blauw) en oranje (geel over rood) tinten.